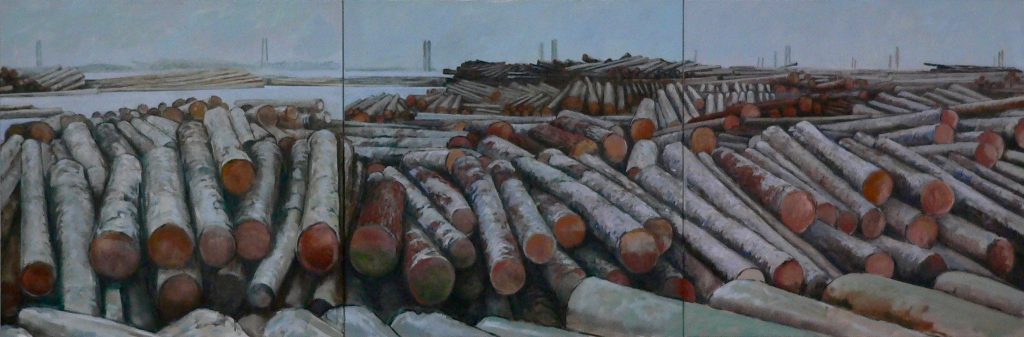

From the The River series.

‘West of Musqueam and South of the University’ is comprised of nine 42″ x 42″ oil on canvas panels, it’s just shy of 32 feet wide. The painting was first exhibited at the Evergreen Cultural Centre and is now in the collection of the Museum of Vancouver. I painted this painting with the intention of presenting the ‘timber’ in a horizontal format, in contrast to vertical trees in a living forest. “It’s a wonder tall trees ain’t layin’ down” was a refrain I remember singing while working on these booms so many years ago. I find it interesting considering that the ancient Pacific North West Coast rain forests stood intact until the arrival of the colonial-settlers, a mere 200 years ago.

The following is the artist statement is from the 2010 ‘Cut Blocks, Stacks & Bundles’ exhibition at the Evergreen Cultural Centre:

The Ditch / The North Arm of the Fraser

This series of paintings and sculptures began on the Fraser River in the late seventies. Back then I was fairly new to the hard and fast work on the river tugs: twelve hour shifts, mostly nights, seven days a week, one week on and one week off, sometimes weeks straight at a time.

As I recall, we were running light, against the current, our tug threw a hefty wake over the still, dry side sticks of the booms secured on the south side of the river. Logs inside the booms rose and fell in the arc of our wake. It was one of those rare, beautiful, early summer mornings, up past Barnston Island. A mist from the night before hung low over the tree shaded areas of the river and the day promised to be hot and sunburn intense. We were checking boom identification tags for numbers and the the heavy, steady freshet slammed hard into the southern bank from around a big, wide northwest bend in the river.

I spotted them on the south bank, back ends rising up, tall river grass and alders growing out of their trunks. The old cars were facing down, front ends invisible under the turbid water. I remember the pale brown river silt and the green brown algae on the faded, desaturated paint. The mostly silent, sometimes rippling, muddy current flowed through open windows and manufactured cavities. The old bodies were still stylishly intact after years and years of being there, the rounded curves cast in that heavy, solid metal that cars used to be made of. These stationary, half dry, half wet vehicles rested there, oddly perched in the mud and the flora of that bank. They formed a breakwater barrier, like the days of the week checking the flow of time. Someone, probably a farmer, put them there, hoping to keep the river from dissolving that part of the bank.

It took a few days for that vision to really sink in. I had recently graduated from the Ontario College of Art and over the next few years I would continue to work on the shift tugs and paint pictures of abstracted water surfaces after my favourite artists, away in my studio, during my time off. And we got a lot of time off in relation to the intense hours at work, that’s why I took the work in the river in the first place; it gave me more time to direct towards my painting than any other type of work.

But over the next few years I grew restless with abstraction. I made increasing efforts to incorporate direct experience into my paintings. Images of industry crept into the iconography, competing with the formal, painterly aspects of the medium. I became more and more concerned with the industrial landscape I encountered further down river in the North Arm.

This shift in focus was not an easy or seamless one. It proceeded in fits and starts: sometimes the iconography and the handling got too heavy, other times too refined and removed. Over time, I found myself turning to sculpture – in tandem with drawing and painting – in order to reckon with the multifaceted aspects of the subject matter. Sculpture introduced new problems and possibilities, an interesting counterpoint that allowed me to address, with humour, the depressing symbolism of cars stacked up and piled upon each other.

I continued to work on the river, mostly the North Arm, for the next 15 years. We who worked on the river referred to the North Arm as “the ditch” The ditch remains a compelling, and sometimes beautiful place. It’s a site of memory, meditation and inspiration for me.

And it’s a sign of our time.